All of us spend our days in a set of interconnected and nested systems. Sure, the ecosystem and the capitalist system, but equally our families, our friend groups, our workplaces. All of them can be reduced at their essence to stocks that are alternately growing, shrinking or being held in equilibrium, in response to flows and feedback loops. Which means that you could, if you were so inclined, govern your life entirely by systems thinking — model everything as systems diagrams and graphs of system behaviour over time.

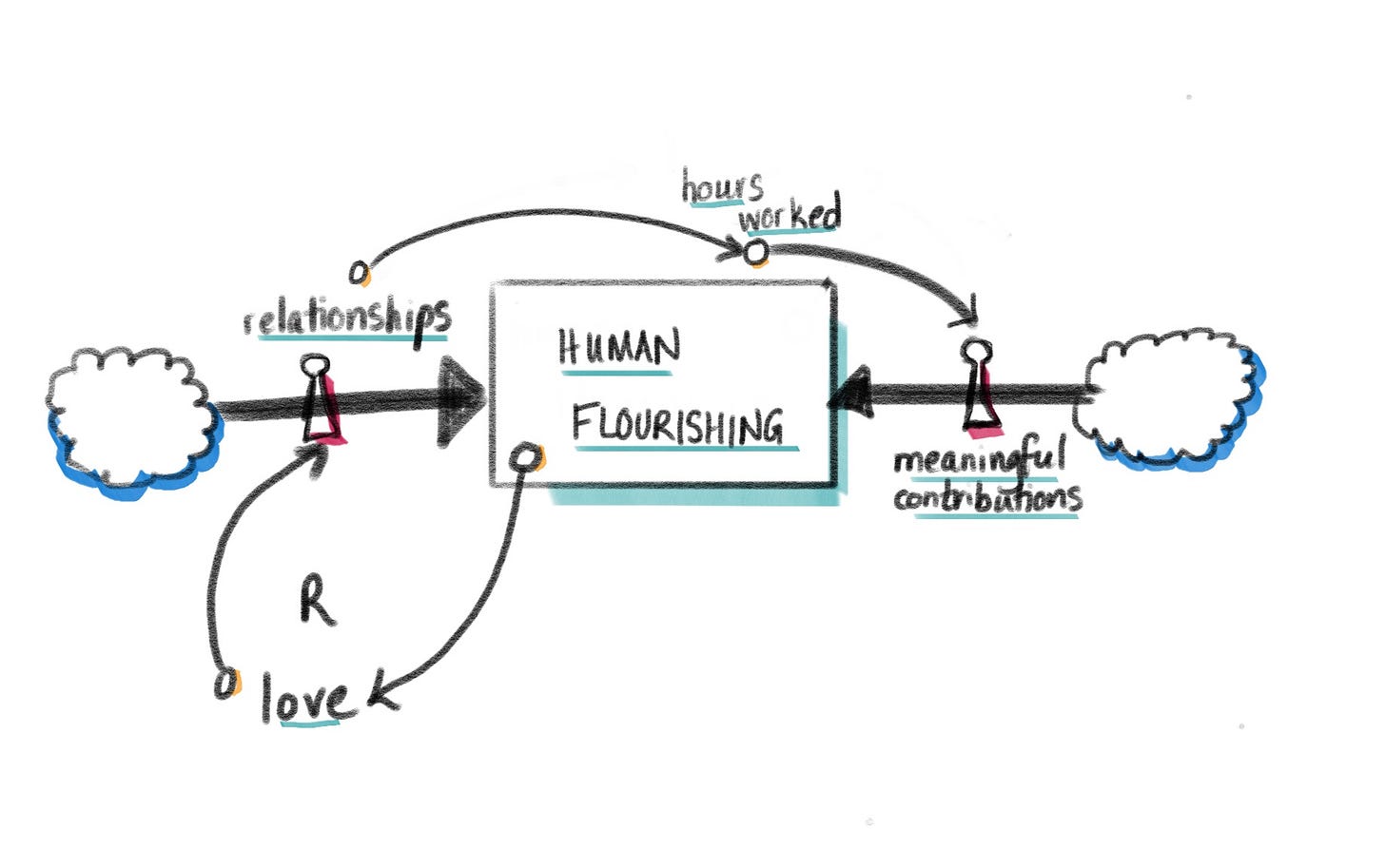

If human flourishing is our stock, are relationships and meaningful contributions to the world the flows? Is love a reinforcing loop? Do hours worked both feed contributions and deplete relationships? It’s a work in progress, I’ll admit. But it’s hard to come away from Donella Meadows’s classic book Thinking in Systems without the conviction that systems thinking might hold the secret decoder key for the universe.

Published posthumously, Meadows’s book begins prosaically enough — basic terminology, how to read a stock-and-flow diagram, the canonical system archetypes. But as she outlines the properties of systems, their behaviours, their leverage points, we start to realize that the fundamental system dynamics are everywhere, if only we would notice them and learn their lessons.

“Systems thinking transcends disciplines and cultures, and when it is done right, it overarches history as well.”

Systems people, Meadows tells us, are fanatical about delays — that gap between a system changing and our perception of it. How innate is the instinct to respond quickly and forcefully to perceived changes? And how wrong-headed in the cases where systems have delays (which is to say almost all of them). System thinkers know the result is predictable — the more swiftly and decisively you act to a perceived change, the more instability you tend to create, as the system overshoots and oscillates wildly between ever-more pronounced extremes. This will not come as a surprise to anyone living through the delays between people catching an infectious disease and getting diagnosed, and increasing case counts affecting public health policy. Conversely, system thinkers avow the necessity of foresight. If you wait until a change is obvious, you will have missed the window of opportunity. Counter-intuitively, the wisdom of systems thinking suggests being swift and decisive based on foresight and potential, but more measured in response to actual events.

The problem with events, according to Meadows, is that they are beguiling in unhelpful ways. We want to see the world as a series of events and put almost all of our focus there. But instead, we should spend energy on understanding the relationship between events, underlying system structure, and long-term behaviour. Resilience is one such behaviour: naturally present as reinforcing and balancing loops return a system to equilibrium after an event.

“Resilience: The ability to recover strength, spirits, good humour, or any other aspect quickly.”

But it’s hard to observe or measure resilience, and thus easy to inadvertently sacrifice it in service of some other goal, like productivity, or efficiency. It’s only when systems fail to recover that we realize resilience was lacking. Systems thinkers, then, might anticipate that the true reckoning of the fall-out of COVID-19 won’t be apparent until we return to “normal.” Will our systems — the economy, the polity, the workplace, the household — find a new, stable equilibrium after all that has transpired?

And indeed, for all of us, the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the arbitrariness of how we typically daw system boundaries — not just in how outside forces like novel viruses affect our personal and professional systems, but more importantly how our own actions have knock-on effects far beyond our normal circle of concern. With pandemic public health guidelines, we had to re-draw those system boundaries and consider how our personal choices — to wear a mask, to socialize, to frequent establishments — affect public health more broadly. Systems thinkers know the necessity of drawing these boundaries. “We have to create boundaries for sanity and clarity,” writes Meadows. But the consequences of those boundary choices are far-reaching. When a start-up makes a platform to facilitate renting short-term accommodations from individuals, they draw their system boundaries to exclude the question of long-term, affordable rental housing. And then they reap the private benefit from the value created, while socializing the public harm to affordable housing stock. More broadly still: “economics evolved at a time when labour and capital were the most common limiting factors to production,” so that is where capitalism has drawn system boundaries. But that means leaving things like carbon emissions, clean water, and dump space outside system boundaries, to say nothing of liberty, equality, and human flourishing. Meadows’s remedy for this is twofold:

- Being more conscious and deliberate in drawing boundaries with reference to the questions we’re asking and the problems we’re solving; and

- Looking for opportunities to “expand the boundary of caring,” and make a regular practice of shifting the typical boundaries of our systems to better understand our independencies and our opportunities.

It is on this note — advice for living in a world of systems — that Meadows concludes the book. The advice is both pragmatic and the philosophical; the kind I want to carry with me so it shapes how I live and work in the world. I want to celebrate it all — embrace feedback and iteration! Be transparent with your mental models! Use language with care! I took particular heart from her advice to celebrate complexity. The modern world has a steady drumbeat for simplicity, but some of the most beautiful things (a Gothic cathedral, a symphony, a Persian rug) are messy, embellished, and fractal. Meadows gives us permission to not overprivilege straight lines and smooth surfaces, and revel in complications. And then, at the last, she exhorts us to not “erode the goal of goodness.” To continue to hold ourselves and the world to the highest ideals for morality and goodness, fighting the drift to lower standards at every turn, and using bad behaviour as an occasion to recommit to high expectations.

“Living successfully in a world of systems requires more of us than our ability to calculate. It requires our full humanity — our rationality, our ability to sort out truth from falsehood, our intuition, our compassion, our vision, our morality.”